Full Transparency

Our editorial transparency tool uses blockchain technology to permanently log all changes made to official releases after publication. However, this post is not an official release and therefore not tracked. Visit our learn more for more information.

Over the past few years, you’ve heard about disputes between Pay TV providers and local broadcast TV stations during renegotiation of so-called “retransmission consent” fee agreements. In extreme cases, you’ve seen local TV stations pull their channels from Pay TV providers’ systems when they’re dissatisfied with the progress of those talks – at the expense of Pay TV customers.

We believe it’s important for you to understand what’s at stake with these agreements, because the increasing cost of retransmission deals and video content are making Pay TV services more and more expensive for everyone.

The following article was written by Richard Greenfield, a media and technology analyst at BTIG, a global financial services firm. It was originally published on August 12, 2013, on the BTIG Research blog (registration required).

If you have questions regarding Mr. Greenfield’s post, please contact him directly:

Email: rgreenfield@btig.com | Phone: 646-450-8680 | Twitter: @RichBTIG

The Disequilibrium of Power: How Retransmission Consent Went So Wrong & How to Fix It

By Richard Greenfield

Technology, Media and Telecom Analyst | BTIG Research

August 12, 2013

In recent weeks, many investors and industry executives have openly questioned our positioning in the Time Warner Cable vs. CBS debate, generally surprised that we would seek so vocally to deny broadcasters their inalienable retrans fee right. We analyze every battle individually and focus on where the relative leverage lies.

In DirecTV vs. Fox in a late 2011 blog post, we stated “DirecTV Must Cave” and questioned: “Why Do Distributors Keep Entering Wars They Cannot Win?” as DirecTV was negotiating FOX retrans and carriage of the Fox Sports RSNs, FX, Nat Geo, etc. While we perceive the leverage in the Time Warner Cable vs. CBS battle as more balanced for a short period of time, we have a more fundamental concern over how retrans has morphed over the past several years.

How Can Broadcast Networks Rely on Retrans, if Retrans Was Intended for Local News?

Broadcaster networks and stations now state they simply cannot survive without a dual revenue stream model (advertising plus retrans) and that they should be paid affiliate fees at the top of the “cable network” heap (disregard for the moment that they are free over-the-air broadcasters). CBS’ Les Moonves talking about retrans and how much the CBS network could extract from affiliates in reverse retrans at a June 2011 investor conference:

“the sky is the limit…every affiliate and every affiliate group needs to be treated differently…I had a conversation with Rupert [Murdoch] and Chase [Carey], and they said the same thing. If a station is really looking at what’s bringing in the money, it’s the NFL, it’s American Idol, it’s CSI, it’s the prime time strength. It’s not the local news or Regis and Kelly at 9 AM that’s bringing in the big bucks.”

Yet, when retransmission consent was conceived, the entire focus was on ensuring the health of local news and information, not national programming such as sports and entertainment. The concept of reverse compensation or “reverse retrans” where the local broadcaster remits a portion of their retransmission consent fees to fund the national broadcast network did not exist, with members of Congress specifically citing the local vs. national focus of the 1992 Cable Act during Congressional Debate on the bill:

Congressman Rod Chandler:

“…retransmission consent is a local issue. It affects broadcasters and the public service which they provide to their communities. It is an issue of local stations, carrying local programming and news about local interests.” [January 1992]

Congressman H.L. Sonny Callahan:

“This right of retransmission consent…is a local right. This is not, as some allege, a network bailout for Dan Rather or Jay Leno. Networks are not a party to these negotiations, except in those few instances where they own local stations themselves.” [July 1992]

Senator Daniel Inouye (sponsor of the 1992 Cable Act):

“…universal availability of local broadcast signals is a major goal of this legislation…to ensure that local stations remain viable well into the future to continue to provide local service to cable subscribers and non-subscribers alike.” [July 1992]

Furthermore, we have a hard time believing that broadcast networks cannot generate great programming without (reverse) retransmission consent fees. When we think about the iconic shows of our childhood from The Cosby Show to Cheers to Hill Street Blues to Seinfeld, broadcasting flourished and retrans did not even exist (let alone reverse retrans). Marquee content has largely shifted to basic and pay cable and is even emerging via digital platforms. Think for a second, what was the last big “risk” taken by broadcast TV? Probably NYPD Blue in 1993. While we love Modern Family, my kids adore Dancing with the Stars and The Voice and we are looking forward to the return of 24, it is hard to say the best television is on broadcast today. Now it’s HBO’s Games of Thrones, Showtime’s Homeland, FX’s Sons of Anarchy, AMC’s Breaking Bad and Netflix’s Orange is the New Black, just to name a few, “nuf said.”

The Creation of Retransmission Consent in 1992

Congress created the retransmission consent negotiation process as an alternative to unpaid, must-carry as part of the 1992 Cable Act. Despite robust advertising revenues, broadcasters saw the rise of cable systems as an opportunity to use retrans to further increase profitability and lobbied Congress to allow negotiated retrans. While there was a building concern in 1992 that the growth of cable networks and regional monopoly cable system operators would hurt the broadcast industry, one might wonder why Congress cared so much about giving local television stations the option of negotiated retrans versus must-carry. The answer lies simply in greed, politics and lobbying power. Remember, in 1992, local TV newscasts were vital to Congressional election campaigns.

On October 5, 1992, Georgia Congressman Newt Gingrich, who opposed the 1992 Cable Act, stated ahead of the vote to override President George H.W. Bush’s veto, the only override of GHWB (via Congressional Record of the 102nd Congress):

“Retransmission means the cable companies will now pay the broadcasters to broadcast on cable something which the broadcasters have already sold advertising to pay for, and if you are a cable viewer you will both get to watch the advertising and pay a higher fee”

“I just want to read into the record one sentence out of a letter I got from a TV station which will explain to a lot of people what is going to happen tonight. This is what one of my local stations said: `When you are looking for exposure to your constituents, you look to television stations like station X. And yet you are voting against us.’ I think that is the most overt example of blackmail by a television station I have seen. I am confident it is against the Federal communications law, and yet I know that Member after Member after Member has had phone calls that have said in effect, `If you vote against the broadcasters getting richer, you will in some way be punished.’”

That same night Massachusetts Congressman Edward Markey responding to Gingrich’s claims (worth noting Markey, now a Senator, has been a vocal critic of carriage drops and fee disputes the ’92 Cable Act he supported has provoked):

“…those on the other side who are arguing that this bill will increase rates have a difficult obstacle to overcome, because we have three levels of rate regulation: One, we regulate the basic rate; two we regulate the tiers that include the Disney channel and ESPN that are immediately above the basic rate and we build in a cost-based regulation for the clickers…protections for rate increases will stay on the books, and the FCC is mandated in this legislation to ensure that there are reasonable rates for every citizen in America…join with all the Members here who want to protect the consumers of America against cable rate gouging, and vote tonight ‘yes’ to override the President’s veto.”

Retrans Then and Now

When TV stations owners began to shift from “must-carry” to “negotiated retrans” in 1993, leverage between the two opposing sides was fairly balanced, with no major blackouts ensuing. Cable operators were regional monopolies controlling consumers’ access to multichannel video programming, while local television stations had the exclusive regional access to a television network’s high-value programming, particularly sports content. Both sides needed each other and business flourished for all.

Fast-forward 20 years later, the media landscape has been dramatically transformed, yet retransmission consent is still governed by 1992 legislation. The original balance of power between cable operator and local television station has all but vanished. Cable operators’ video monopolies are now a distant memory, with many television markets now served by four or more multichannel video distributors. On the other hand, local broadcast television station owners continue to have exclusive access to a television network’s programming.

Broadcast station owners’ leverage has increased even further due to rampant industry consolidation and the use/extension of local marketing agreements (LMAs) and shared services agreements (SSAs) to negotiate retrans on behalf of multiple independently owned broadcasters in the same market. Despite broadcast stations’ ability to openly collude to drive up the cost of retrans, multichannel video programming distributors (MVPDs, which include cable operators) are not legally allowed to jointly-negotiate retrans. While MVPDs have certainly consolidated since the creation of retrans, the largest company, Comcast, has reversed its position on retrans since the government approved its purchase of NBC Universal. Comcast’s need to improve NBC profits has made it an advocate of retrans fees, despite the harm imposed on its far larger cable operations. Comcast’s 180 degree turn has significantly weakened the lobbying efforts of the MVPDs to reform retrans.

As if the current retrans leverage imbalance was not skewed enough, the broadcast TV station groups owned by the broadcast networks, so-called owned and operated stations (in contrast to affiliated stations) now utilize their market power from vast cable network holdings. Broadcast networks such as ABC have suffered severe ratings declines and shifted their marquee programming to cable networks, with Monday Night Football moved to ESPN from ABC. However, with ABC’s parent company, Disney owning both ESPN and an ABC station group, not to mention the Disney Channel, Disney is able to pool all of its programming power together when it negotiates with an MVPD (similar to what CBS is doing with Showtime in the current Time Warner Cable dispute). Combining broadcast and cable network programming heft to drive retransmission consent fees was never envisioned when you read the 1992 Cable Act.

Should Free Over-The-Air Broadcasters Generate $12 Billion Annually in Retrans?

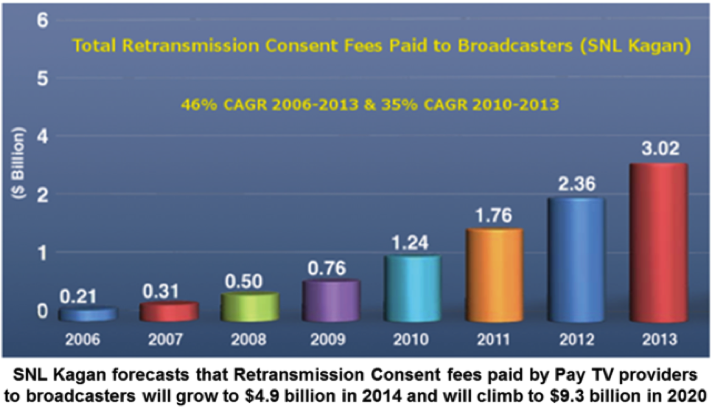

Retransmission consent fees paid by MVPDs four-to-five years ago were under $0.15 per subscriber per month. These fees have risen to upwards of $0.50-$0.75 per sub per month today. Now CBS, aided by its ownership of Showtime, is seeking $2.00 per sub per month from Time Warner Cable. If all broadcast TV station owners are able to achieve the $2.00 monthly fee, the total annual retrans payments across 100 million multichannel television households will be $12 billion. This $12 billion would essentially be an annual tax on consumers to receive television signals that are broadcast over-the-air for free, using spectrum that was given to local TV broadcasters for free and who are supposed to operate in the public interest. Unlike federal/state taxes that benefit the public interest, this tax is simply going to pad broadcaster profit margins.

Broadcasters’ counter that their programming remains the most viewed, with far higher ratings/viewers than a cable network such as ESPN, which charges MVPDs over $5 per subscriber per month. We cannot dispute the relative viewership point. However, cable networks such as ESPN do not broadcast their content over-the-air for free, nor do they make the vast majority of their content available online for free. Another distinguishing factor is that an MVPD’s monthly cost of a cable network is defrayed by advertising time, which the MVPD can sell locally. Whereas broadcast stations must be retransmitted in their entirety, as per the 1992 Cable Act, which means MVPD cannot be given local ad slots to sell, offsetting a portion of their retrans cost. Also worth noting that broadcast stations have a unique public interest requirement, while cable networks do not. If broadcasters want to be paid like cable networks, they should forfeit their spectrum back to the government (with spectrum desperately needed) and negotiate nationwide cable network carriage (see our July 31st blog post).

Broadcaster rhetoric focuses consumers on the size of their monthly cable bills and how little the broadcasters see of those fees. Yet, broadcast network/stations owned by larger cable network conglomerates fail to mention how many low-rated cable networks were forced into the basic cable tier utilizing retransmission consent leverage over the past two decades. In essence, retrans fees are significantly higher than meets the eye today. Broadcasters also never reference the billions of dollars spent by the cable industry to provide a high-quality video experience that seamlessly integrates broadcast and cable networks together without the need for an antenna (often extending a station’s reach beyond what an over-the-air antenna yields), which also enables on-demand viewing, in stark contrast to the free spectrum utilized by broadcasters. Lastly, the Internet as we know it today would not exist without the investment made by the cable industry over the past twenty years, which enables broadcast networks to distribute and monetize their content in all new ways.

Broadcasters fundamentally believe that MVPDs will increase monthly video rates to their subscribers, regardless of whether retrans fees exist/increase and they are simply extracting their fair share of an MVPD’s currently “inflated” profit margin. We find it hard to believe new fees such as “sports surcharges,” which is just another name for a price increase would be happening this quickly if retrans demands were less aggressive. While it is possible that lower retrans prospects might push broadcast networks to convert to cable networks to drive affiliate fees more rapidly, we suspect the complexity and time involved to make that business model shift mitigates this risk.

Play Nice or The Government Needs to Get Involved

The leverage between broadcasters and MVPDs is now so lopsided that it often feels like MVPDs are entering battle with paper swords and shields, while broadcasters walk into battle in full body armor carrying bazookas. While the timing of the current Time Warner Cable versus CBS dispute results in somewhat more balanced leverage, albeit only for the next few weeks, retrans is becoming an increasing problem, with consumers suffering the most.

In an ideal world, MVPDs and broadcasters could work out agreements behind closed doors with rational annual retrans fee increases enabling everyone to walk away happy. Yet, the public chafing between both sides is reaching an all-time high, as broadcasters grow more confident that they cannot lose in these battles due to their control of exclusive sports content, along with the government’s complete lack of interest in intervening. Broadcasters are now trying to push the current $3 billion of total retrans fees (shown in the chart embedded at the top right of this blog) toward $12 billion at a rapid rate.

Interestingly, while the FCC in recent years has resisted intervening in retrans disputes, the 1992 Cable Act appears to mandate FCC oversight:

“…govern the exercise by television broadcast stations of the right to grant retransmission consent and…the impact that the grant of retransmission content by television stations may have on the rates for the basic service tier…to ensure that the rates for the basic service tier are reasonable.”

While that is a broad statement and does not specifically address blackouts, this January 30, 1992 interchange on the Senate floor with the sponsor of the 1992 Cable Act leaves no doubt about FCC oversight of retrans disputes:

Senator Carl Levin:

“…the bill does not directly address the possibility that broadcasters and cable operators in a particular market may be unable to reach an agreement, resulting in noncarriage of the broadcast signal via the cable system. I strongly suggest, and hope that the chairman of the subcommittee concurs, that the FCC should be directed to exercise its existing authority to resolve disputes between cable operators and broadcasters, including the use of binding arbitration or alternative dispute resolution methods in circumstances where negotiations over retransmission rights break down and noncarriage occurs, depriving consumers of access to broadcast signals.”

Senator Daniel Inouye (sponsor of the 1992 Cable Act):

“The FCC does have the authority to require arbitration, and I certainly encourage the FCC to consider using that authority if the situation the Senator from Michigan is concerned about arises and the FCC deems arbitration would be the most effective way to resolve the situation.”

Senator Inouye later states even more directly:

“…there may be times when the Government may be of assistance in helping the parties reach an agreement. I am confident, as I believe the other cosponsors of the bill are, that the FCC has the authority under the Communications Act and under the provisions of this bill to address what would be the rare instances in which such carriage agreements are not reached. I believe that the FCC should exercise this authority, when necessary, to help ensure that local broadcast signals are available to all the cable subscribers.”

Time Warner Cable’s negotiating position will weaken dramatically in mid-September, when the NFL returns to CBS and the fall television schedule launches. In turn, with CBS unwilling to accept moderate increases vs. dramatic step-ups, time is of the essence for the FCC to act. If the FCC fails to take action to rebalance the leverage between broadcasters and MVPDs, Congress should intervene, regardless of the threats made to their individual political futures.

We side with broadcasters in the belief that their content is valuable, however, local broadcast retransmission consent legislation was never intended to fund NFL rights acquisition and primetime network programming – Congress wanted to ensure funding of “local” television. We firmly believe more balanced leverage between broadcasters and distributors would aid consumers and a rewrite/update of 20-year old retransmission consent legislation appears more than necessary.

One Idea We Have, But Not Without the Risk of New Problems

If Congress authorized MVPDs in a given market to work together to negotiate retrans the way broadcasters are allowed to utilize LMAs and combine the leverage of their broadcast and cable network holdings there would be far more balance to the retrans negotiations in each market (preventing a broadcaster from playing one MVPD against another). The fear politicians run of advancing this policy would be if it results in broadcast networks abandoning broadcasting altogether to become cable networks, leaving Congress with 15 millions US households with no access to television and a likely shift away from local news and information (as cable networks have no public interest requirement). However, it is worth noting that a meaningful percentage of the aforementioned 15 million Americans proactively choose not to subscribe to multichannel television, meaning they could afford lifeline basic cable if they wanted it. In addition, broadcasters continue to scale back their news operations (utilizing local news sharing arrangements), while cable operators have launched an increasing number of local news cable networks to serve their subscribers/communities.

Richard Greenfield is an equity research analyst for BTIG LLC, focusing on the technology, media and telecom industries since 1995. His coverage ranges from diversified media and entertainment conglomerates, movie studios, online video, cable and satellite distributors and advertising-based Internet media companies. Greenfield is also co-creator of the BTIG Research blog, which provides thought-provoking research and commentary from analysts at BTIG.